A Conversation with Hisko Hulsing

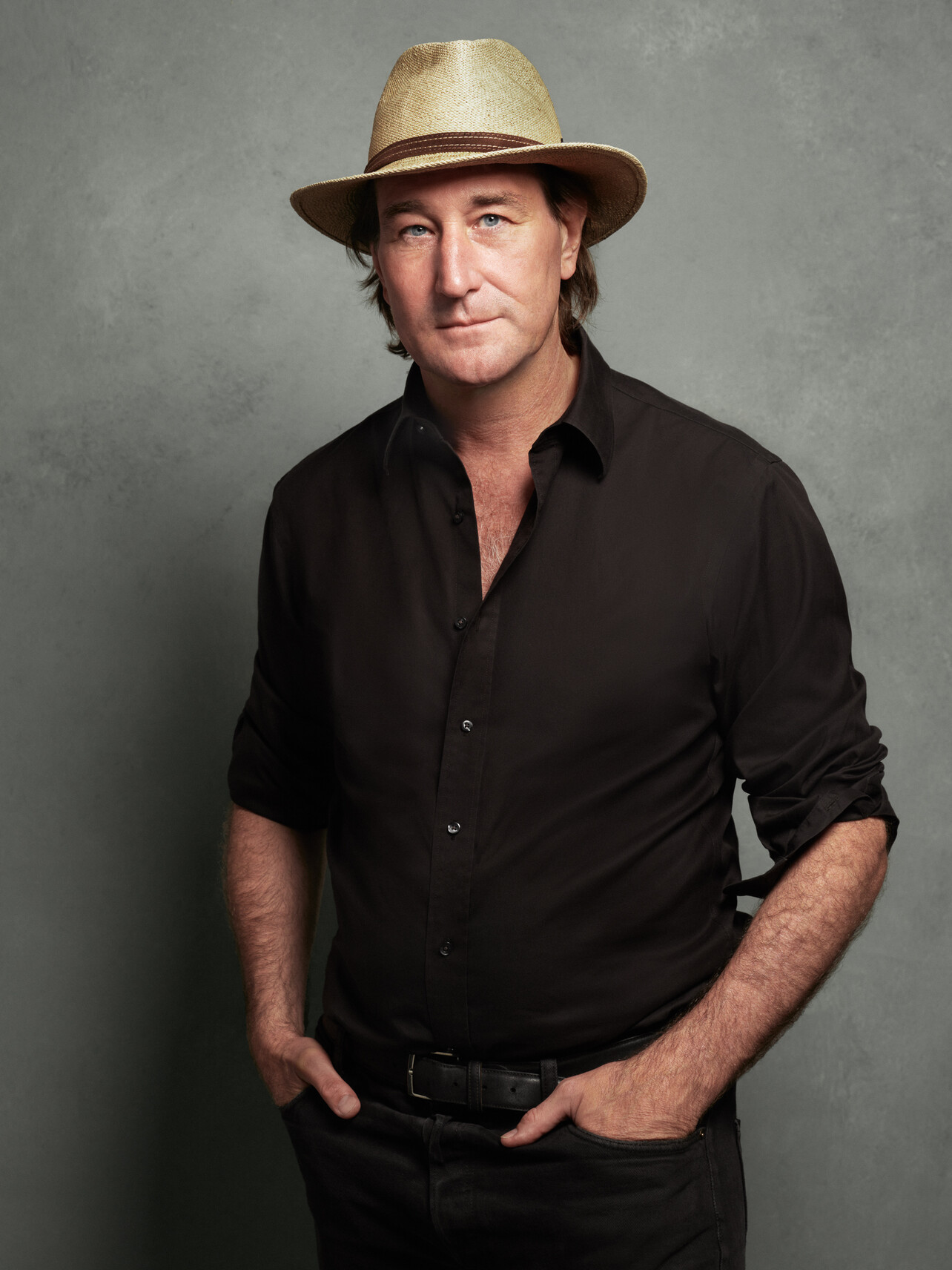

Stefan Stratil from ASIFA Austria, Association Internationale du Film d' Animation, in conversation with MQ Artist-in-Residence Hisko Hulsing (NL). On March 24th, 2025, at 3 p.m., MQ Artist-in-Residence Hisko Hulsing will hold a masterclass at the Under_the_Radar Festival at Raum D/MQ and open his installation “Resurrection” at the animation art showroom ASIFAKEIL.

Hisko, how did you get from an animator to directing big series for Amazon, Netflix and HBO?

When I was 25 I started out like most animators and artists, working from my bedroom, making films and paintings. What I like about animation is that you can combine so many art forms. You're dealing with music, with sound... I make all my background paintings with oil paint on canvas. I'm drawing, I'm thinking about costumes, about lighting, it's a very, very broad thing. So if you make your own films, you're busy with all those different facets of animation, which are all art forms on themselves.

I made a short film called Junkyard which I worked on for six years. Though only 18 minutes long I really wanted to make kind of a perfect short film. When it came out in 2012, it got 25 awards, and it got the attention of Disney, DreamWorks, Pixar and Blue Sky who invited me to show my work. So that short film got me noticed by producers and directors in Hollywood for bigger projects. After Junkyard, I did another Dutch project called Last Hijack. When it premiered at the Berlin Festival, the Berlinale, I knew that it would probably get some attention. So I put Junkyard, which was already two years old, online and luckily it went viral. Apparently someone at The Hollywood Reporter had seen it, and he wrote that Last Hijack featured handsome animation from Hisko Hulsing/Junkyard. So still at the Berlin Film Festival I got an email from Brett Morgen, an Oscar nominated director who is making documentaries in Hollywood. He had just seen Junkyard because of that article in Hollywood Reporter and asked me if I was interested in cooperating with him on a film about Kurt Cobain from Nirvana for Universal Pictures and HBO. That's really where my international career started because I did the animation for that film, called Montage of Heck and it became really successful. It got eight Emmy nominations and it was shown in theatres all over the world, distributed by Universal Pictures, broadcasted by HBO.

So that's how it works. It's like a snowball that gets more and more snow when it's rolling down the hill.

But what was it especially that made people from Disney or other studios get an interest in your films? Was it a certain style or was it because it was very efficient or did it fit in the programs?

Yeah, that's a good question. Well, I think other than most artistic animated films, Junkyard has quite a classic narrative structure. And the other thing that makes it different is that I make all the backgrounds with oil paint. They have a very classical, almost Bambi-like feel that caused a certain nostalgia with studios like Disney because they don't make those kinds of films anymore. Brett Morgen thought that Junkyard had the same dark and raw energy as Kurt, so he liked to use that similar kind of roughness. The harsh story full of emotion and violence makes Junkyard different from most animated short films. The film is cinematic and very realistic because I used a form of rotoscoping, but also very dreamlike at the same time, and I think that combination was very well suited also for Undone, the series that I did for Amazon. So Montage of Heck, the film about Kurt Cobain, was nominated for eight Emmy Awards. but also nominated for an Annie Award, and the producers who are working for Michael Eisner, who used to be head of Disney, were nominated for Bojack Horseman. And during the awards ceremony they saw a little piece of my animation for Montage of Heck.

A couple of weeks later I gave a lecture in Berkeley, and they came all over to Berkeley from LA, to have breakfast and pitch Undone to me. Their pitch sounded like a good and ambiguous script, in which it was not clear if the main character was time-travelling or if she was schizophrenic. It was exactly the kind of film that I wanted to make, but I doubted if I could do it. I told them with Montage of Heck, I had to do almost 10 minutes of animation in only four months, which nearly killed me. I was working 15 hours a day, and drawing, painting and managing 25 people without a producer was one big chaos. After that film I actually wanted to quit animation because it was all too much. But they were pretty sure about me, they invited me to LA, where I had a five hour conversation with the writers and showrunners, Kate Purdy, and Raphael Bob- Waksberg, and it really clicked. They decided that I would be the director of the series. They told me not to worry about the production, they would set it up around me. And they also were fine with me doing most of the work in Amsterdam. So we connected to Submarine, a studio in Amsterdam, that hired 100 people to work on Undone. We did the live action recordings with the actors for rotoscoping. We had really good actors like Bob Odenkirk from Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, and Rosa Salazar. I had to fly back and forth between LA and Amsterdam seven times to direct the actors on the set, 13 hours a day. And then I would go back to my apartment and do all the briefings on the animation that was being done in Amsterdam and in Texas. So I was again working 15 hours a day as with Montage of Heck, but when it's well organized it's not a problem when you have to work hard.

Back in Amsterdam I would train a team of 10 painters who had to paint in my style with oil paint. I didn't have time to draw anymore apart from the thumbnails, and for the rest of the time I was just talking and talking and talking (just like now).

Anyhow, when Undone came out, it became the best reviewed animated series of 2019 according to Rotten Tomatoes, because we had a 100% score. We had solely good reviews from the New York Times and Time magazine etc. We were in many top 10 lists. So that's how Netflix and Warner Brothers found me to do an episode for the Sandman, a live action series with one animated bonus episode that they wanted me to direct. Both these shows were very successful and we had a second season of Undone.

When we were finished I actually made quite some money and I was certain that there had to be many studios wanting to work with me, because of the success of Undone and Sandman - but that didn't turn out to be true.

I realized that what I am doing is kind of a niche. Making animation for adult people is not a common thing. If I would have been successful with a children's movie it would be much easier. There's just not a lot of animation for adults. On television or Netflix or Amazon or in the theatres there's hardly anything.

Rotoscopy allows you both to work efficiently and to establish a realistic level that you need as a contrast to the very fantastic animation scenes.

There were a lot of discussions with the writers in LA about whether we had to make a stylistic difference between flashbacks, dreams, reality or psychosis and I told them that everything should have the same look, so that the audience never knows if what's happening is real or not. Because it's first acted by actors it feels very real. You get all the subtle acting of those really good actors that you don't have in normal animation. But when something really crazy happens it is kind of the other way around. In Undone you might think that a scene in which someone is just having lunch takes place in the real world, when suddenly everything blows up and it turns out not to be real or at least ambiguous. It's a way to confuse the audience about the nature of reality. And that can only work in this rotoscoping style, because everything looks real but feels unreal at the same time.

In the whole first episode, nothing really strange happens. The story is being set up. When you get into the second episode, it's completely clear why it's rotoscoped and why it's animation, because very strange things start to happen and lines between dream and reality are being blurred.

I used to dislike rotoscoping before we made Undone. It was kind of a weird move to get into rotoscoping, but it was the script that sort of demanded it. What we were getting from the actors is something you can never get with normal animation. Most animation is exaggerated, it's not as subtle. Rosa Salazar, who plays Alma, does little things with her eyes that you cannot make up. It's just her personality, the whole way she moves. And if you have an animator interpreting a script, then the animator will do the acting. But animators have a different sensibility, I would say, different to real actors. With really great actors you never know if they're acting or not. The first time i saw Rosa, she hugged me, she started crying and I was overwhelmed and flattered. And then the next day we did a scene and she was just crying on exactly the same moment in every take. I was like, okay, she can just do that. Imagine her to be your girlfriend…

As animators or painters, we have our easel, we have our instruments, we have our paint and our tools, or the computer. The tools of actors are their body, their mind and their soul. And if they're really good, they're in complete control over that. So one of the things that I like about Undone is that it's really well acted and very well written by Kate and Raphael and their team and therefore works on a different level.

With your new project, Resurrection, will it be a similar style or will it be something completely different?

It's completely different. I started this film eight years ago. It was inspired by music by Dmitry Shostakovich and by what was happening in Ukraine. And in Russia. Russia had overtaken the Crimea and people in Europe were not so worried about it at the time. But I was reading a lot about Russia. The way Putin talked about great Russia felt dangerous to me. I saw that there was some sort of fascist movement going on and that there were horrible things about to happen, I remembered a battle at this war in Yugoslavia where they were revenging a battle from 1300. It's fucking insane. It's like getting all those old things out of the ground again. That's why the film is called Resurrection. The resurrection of demons from the past.

I started to make this animatic, which was very different from everything else I've done before, because usually I write a script, a story, and then I make the storyboards etc. But in this case, I wanted to be completely inspired by the music. The film works more as a dream or a nightmare than as a classic narrative. It doesn't have a linear story. Then I started making these huge paintings. Usually the characters are separated from the backgrounds. But I wanted to paint everything and then find out later how I will translate it to animation. It's kind of an insane way to do it. But I just wanted everything to look painted and I wanted it to be a really fascinating series of real paintings at the same time.

And how many paintings do you have already?

30 out of 50. I had to stop working on this film because of Undone and The Sandman, Dream of a Thousand Cats. Two years ago, I started again. I found a producer called Richard Valk. And he really wanted to produce this film because he was completely overwhelmed by the animatic. Nicolas Schmerkin from Autour du Minuit, the studio in France, was also approaching me over the years. I was a bit worried because this film will definitely be expensive because of the mass scenes and the high ambitions. It almost costs half a million euro for four minutes of film. It's really insane. But we're almost there. We almost have the money now.

So the method we're using is that I make all those paintings. Then all the skeletons are animated in Paris in 3D. Six years ago, we used projection mapping to make the 3D skeletons look like they were painted. But now we're using Stable Diffusion, an AI program to stylize the skeletons. We fed Stable Diffusion with all my paintings to train it. The animation is completely done by animators using Blender, the 3D animation software. Then we use all the information from the 3D animation, the crypto map, the depth map, the line-renders to control Stable Diffusion to make it look like it's painted by me. We did a very successful test. So we are confident in the method and I am sure it will be utterly beautiful.

Well, you could let the AI do the last 20 paintings.

No way. No. And that's the thing, you can generate paintings, but what I have seen looks horrible. We only use it to make the 3D animation look like I painted it. But the background is a different, a really different story. The good thing about this crazy and complex method is that I will have a lot of paintings that I can exhibit, for instance, at the MuseumQuartier. So it's kind of a multimedia project where you have real oil paintings, not just backgrounds. And possibly live performances with orchestra.

I can completely understand your joy in having an analog outcome of paintings, something that you can touch and show.

Yeah. Yeah, because, you know, for all my own films, I made all painted backgrounds. But the thing is that the real subject of the painting is missing, because the subject is not painted, it’s animated usually. In my studio I have about 300 paintings. A lot of them are autonomous works some are not. But the main thing is that hey fit within a film. With this film it is different. Each painting is a painting on itself. I am trying to break out of just being known as an animation director. I would also like to be known as a visual artist, as a painter. And maybe being artist in residence in the MuseumsQuartier might help me getting a bit more credit in that field.

We'll try to advertise your work and show it to the world.

That would be cool. People get typecasted and sometimes it takes effort to break out of it.

What I really appreciate in your case, is that an artistic approach combines with a so-called commercial outcome. That is something special.

I guess I’ve just been very lucky, It doesn't happen so much, especially not in Hollywood where there's not a lot of producers who take those kind of risks. In Europe more people take those risks, but I believe that they are not doing enough to get an audience to come and see them. What I like about the American approach is that when they do it, they also advertise it. When we did Undone, there were huge billboards and the whole IMDB page was all about Undone. If you don't do that people are not going to watch it. There’s that kind of spirit where they really want to make money and sometimes if you're lucky, they want to make something artistic at the same time. And if that goes together, then you're being very lucky. It doesn't happen much. But right now, I'm working on two other projects. One of them is secret, so I cannot talk about it. But it's for a really big studio. It is also for adults or young adults. And it's very surreal. And they want me to direct it and to do it in my style. And I'm also storyboarding a whole American feature film. A very surreal one. Super nice. So, lots of work and hardly an income.

Well, maybe you can say something positive as a final word.

Oh, the final word. Well, it's what I said before. It's like, you know, making animation gives me such a rich life. I mean, not only to be able to work on so many different things. Animation, film, paintings, drawing, music. I composed orchestral scores for two of my films.

We didn't talk about the soundtrack that is very important for you. But if we start now…

No, no, no. I just wanted to say that it's a very broad profession. And the other thing that I really like... Okay, I can say something which might backfire on me. But I'm not the biggest animation fan in the world. What I really like about animation are the people. I like the animation world very much. Like you and me, we met in China. We are so lucky that films bring us all over the world. We spent the whole night talking about Brazilian music. So a Dutch guy, an Austrian guy are sitting in a Chinese restaurant in Xiamen to discuss Brazilian music. That's kind of weird and interesting.

Yeah, that's nice. When you like something, then you get very picky. You have a high expectation. And I think that's good. You don't have to like everything about animation.

No, no. The more you see, the more you see things that are kind of the same. And you get bored by it. When I started out in animation, I was like a sponge. I wanted to see everything. And now I'm like, oh, I'm not going to the newest Disney film, in no fucking way.

I'm also with one foot in the commercial world because I did storyboards for more than 120 advertising companies to make money. And I don't like that world at all. And then there's the art world. A lot of people who are very good in talking and bluffing, but it's not my world. The film world is a lot of egos. What I like about the animation world is that animation directors often have a very broad interest. I know animation directors who know a lot about opera or about classical music or about jazz or about bossa nova. And they're often... what's the right word? Modest. Most animation directors or animators are very modest because you cannot bluff your way into being an animator. You just have to deliver the goods. You cannot fake it. It's really hard work.

Maybe being not too modest helped you getting successful with animated series.

Yeah, I think so. And also when you're directing 300 people, then there's not much time left to be insecure or modest because people are depending on you. So you have be clear and tell them what they have to do. It can change one’s personality in a way which is not always positive, I think.

That's interesting. But you have to be a good communicator anyway.

Yes, you have to be a good communicator. Maybe I should be more modest, but in a way, it's not helpful. And especially in the United States, in LA, it's really like the way people sell themselves. Look at Trump. Trump is the most horrible example of that, like how wonderful everything he does is, you know, but it's a part of their culture to be kind of a secondhand car salesman.Like yesterday, when he was trying to sell the Teslas in front of the White House. You have to see it, it's fucking insane. Now we know he's a secondhand car salesman.

Tesla is going down because of Elon Musk, so he's trying to sell Tesla’s in front of the White House. It's really insane. Glad to be a European right now!

Stefan Stratil from ASIFA Austria, Association Internationale du Film d' Animation, in conversation with MQ Artist-in-Residence Hisko Hulsing (NL). On March 24th, 2025, at 3 p.m., MQ Artist-in-Residence Hisko Hulsing will hold a masterclass at the Under_the_Radar Festival at Raum D/MQ and open his installation “Resurrection” at the animation art showroom ASIFAKEIL.