"There's this faith, that photography will solve some problems in the world."

Valter Ventura was Artist-in-Residence in January 2019 and talks with EIKON's Nela Eggenberger about his work.

As the winner of the 2018 Artist-in-Residence Prize, initiated by Q21 in collaboration with the viennacontemporary art fair and EIKON – International Magazine for Photography and Media Art, the Portuguese artist Valter Ventura (b. 1979 in Lisbon), represented by the Kubik Gallery, was invited to live and work for one month in one of the largest districts for contemporary art and culture in the world, the MuseumsQuartier Wien. Nela Eggenberger (Chief Editor EIKON), who was member of the jury together with Matthew Stephenson (Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Photographers’ Gallery), Sabine Winkler (curator), and Elisabeth Hajek (Artistic director frei_raum Q21 exhibition space / Artist-in-Residence Program), met him in his studio to talk about his preferred artistic medium.

Nela Eggenberger: Valter, initially you studied art history at the University of Lisbon, after which you completed a photography course at the independent art school Ar.Co. In 2016 you co-founded the HÉLICE school of photography and you also teach photography in other institutions. Above all you are an artist who is exploring the photographic medium from different angles. What makes photography so particular for you? Where does your original interest in the medium come from?

Valter Ventura: Well, I could talk for hours about so many aspects that I find interesting in photography. One reason is because it’s the medium I know the most, it’s the one I have studied and the one I’m still working on. When I’m taking pictures or when I see exhibitions such as in the galleries you recommended me to visit here in Vienna, the photographs make me wonder about the things I’m seeing, which is not only just the thing that I’m seeing, but also the practice behind it.

Are you talking about the technical aspect?

No, generally speaking. One interesting aspect is that it has this mechanism to disguise itself and to absorb other narratives or to open other ways to see the world. It appeared in a specific moment in mankind, when there’s also the substitution of religion by science. So there’s this faith that photography will solve some problems in the world. The camera is a very objective eye and gave answers to questions that were never asked before. For example, right at the beginning, one of the fascinating things was that we found out how horses gallop. Mankind has been seeing horses galloping since the prehistoric times and nobody could answer the question of whether all the legs were in the air at the same time. The painted presentations of running horses gave you the notion that they were spreading all their legs far apart, because the artists wanted to give this idea of speed. And then suddenly photography appeared and resolved this question. It has this kind of appearance of a scientific proof. After the photographs by Muybridge all representations of running horses changed. So what I’m trying through my artistic practice is to take a step back and question the very thing that I’m doing: What are the applications of doing this with a machine, or does some aspect of the machine have some influence of how this is done? How is it perceived? Would the motif look the same as a drawing or what’s the difference? What’s the difference between having an original or an endless copy? These are some of the many questions that I find appealing.

In your work a preference for the old analogue techniques is clearly noticeable. In Observatório de Tangentes (Tangent Observatory), for example, you took the invention of the fusil photographique (photographic rifle) by Etienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904) as a reference point for your work. Why do you focus on such old apparatus in a world where the physical is becoming less and less?

Maybe it comes from studying the history of art or helping in archaeology for so many years. My idea is always that you must go back to the starting point to understand the whole story. I was asking myself: why do we use so many conceptualisations about hunting and shooting in our understanding of photography? In the Oxford Dictionary I found the term “snapshot”, which was originally a term invented by hunters – an intuitive shot that was made without aiming. And since the invention of photography the term has almost exclusively been used as a photographic term. More or less at the same time, Etienne-Jules Marey invented the first portable camera apparatus, which he called the “photographic rifle” – it’s connected with the idea of photography as hunting. Jeff Wall said in an interview that most of these early pictures were staged to give you the impression that they were made by a “photographer-hunter”, when they were actually made by a “photographer-farmer”. And also, the images that really impacted the world were the ones that had a relation to this imagination. For instance, remember the death of the Republican soldier by Robert Capa.

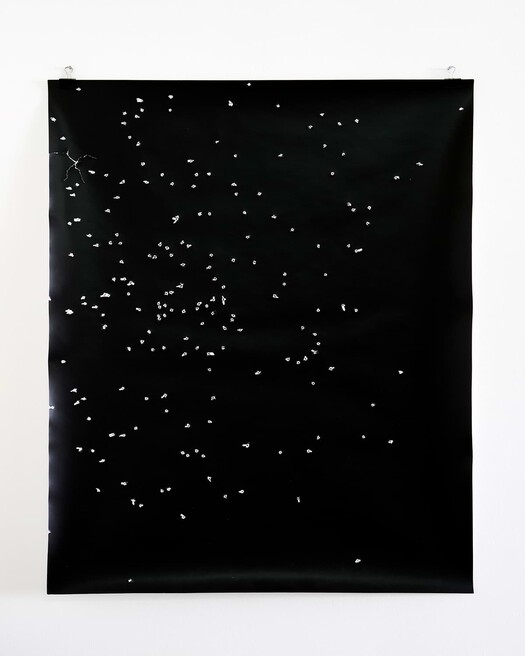

Concerning my project “Tangent Observatory”, a starting point was when I found the replica of the “photographic rifle” in Lisbon, in an exhibition at the Cinemateca Portuguesa, the Cinema Museum; I was allowed to photograph it and print it at a 1:1 scale. Another starting point related to this project was trying to find objects that had been shot. I went to a shooting range, where I collected clay pigeons and tried to put those that had already been shot back together, like an archaeologist. But the project is also about stressing the idea of shooting and shooting things that have already been shot. When I was there, I met some hunters, who I asked – in return – to shoot at photographic paper. Just like the print, which is also a direct outcome of a shot. Afterwards I took it to the laboratory and developed it. In the end I got a result which in terms of photographic discourse is the exact same thing as a photo.

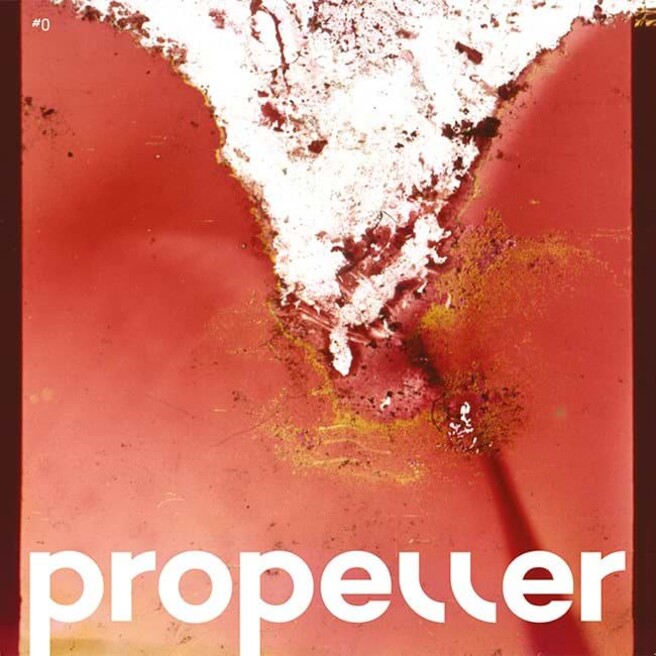

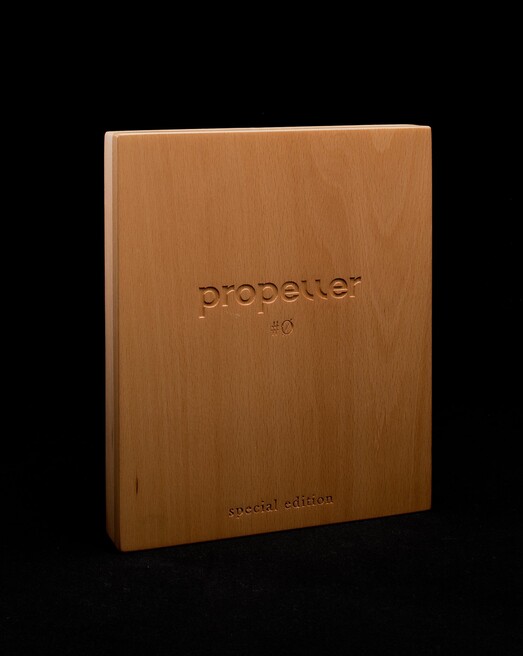

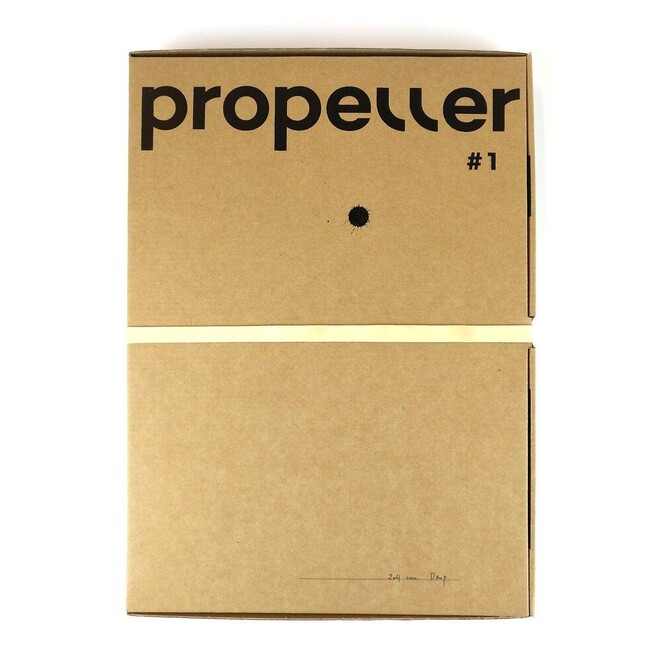

You are one of the founders of the art magazine Propeller and you publish editions yourself. Why do you pay so much attention to producing publications?

In the nineties, when I was studying, and teachers showed important works to us students, they always showed the book. To me this was amazing, because you don’t have the opportunity to see a Jeff Wall in class, but if a book was brought, for instance a copy of Robert Frank’s The Americans, it’s equal to its original. The students can exactly experience the view of the artist by looking at photo books. A publication also makes the actual work accessible to more people. I believe books give you the opportunity to spread your work as you intended it.

The history of Propeller started, when a close friend of ours, Sofia Silva, was trying to establish a magazine related to photography, but she lacked support and a platform. So we invited her to HÉLICE and realised it together. It’s a very specific project, in a way it’s a crazy project… it comprises all of those things that you had better put on a not-to-do list. We had no previous experience in publishing and made it totally by hand. So the production costs were pretty high. Propeller seems more like an art book than a magazine and it only contains unpublished materials. So that’s why most of our contacts, even international ones, are amazed by it and interested in collaborating. For instance, some of us knew Lynne Cohen, a Canadian photographer who died four years ago. We contacted her husband and told him we were interested in involving her. So he gave us unpublished work for the issue. It was a really important moment for us and in contemporary photography as well.

Thanks to this residency you are able to gain a deeper insight into the art scene in Vienna. How important are such experiences abroad for you in general and what would be the ideal output?

So far the output has been great enough by itself. I have the opportunity to stay for one month just thinking about the point that you are trying to make with your work. I am surrounded by people who are really showing interest in the work I’m doing. I spend time with people who are in a similar situation as I am, the other Artists-in-Residence, who have different projects and come from different countries and conceptual contexts. These experiences all together put you into an amazing state of mind. I’ve been able to see an exhibition at the Volkskundemuseum, they have a huge collection of pictures from photo albums from the 30s to the 50s. The latter raised the question about why people back then photographed themselves on vacation and so on, at this very specific moment: can photography be a way to abstract yourself from your reality?

If you had the chance to present just one single piece of your work to a very important person in the art scene, which one would you select? Do you have something like a “masterpiece”?

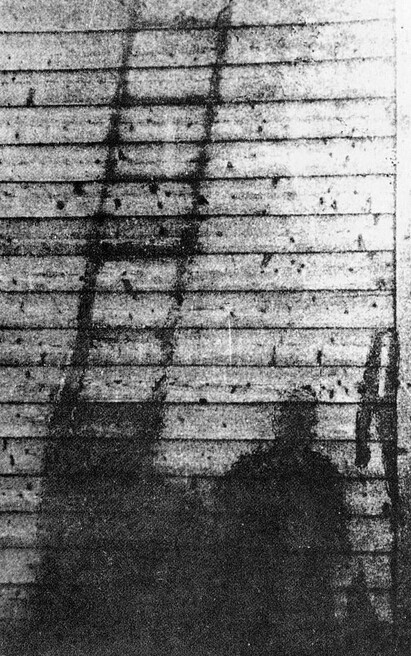

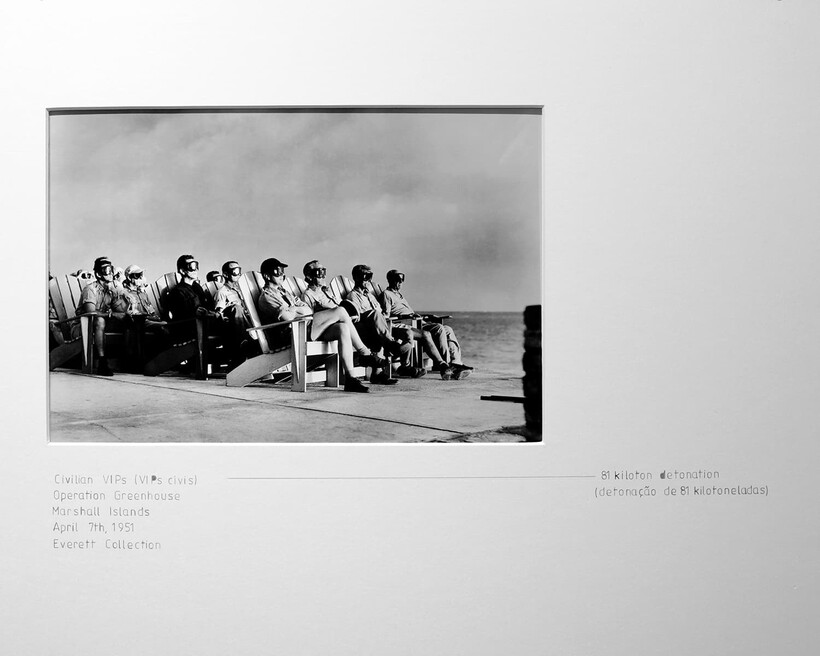

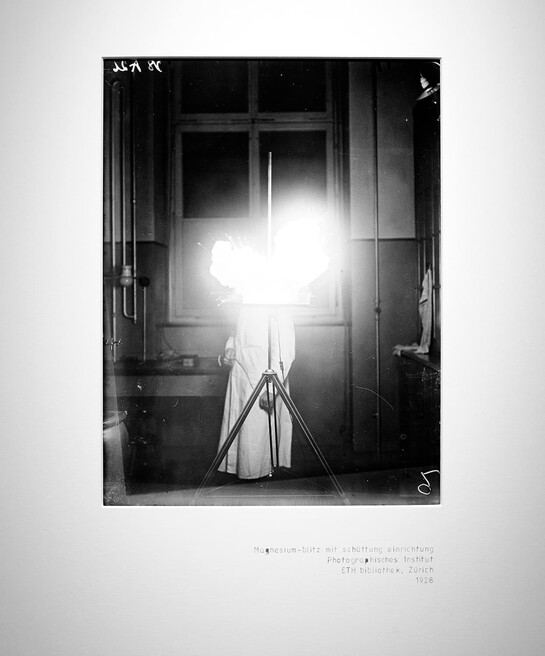

I think the work describing most of my interests is the Compêndio de Observações Fotográficas (Compendium of Photographic Observations), the Observatório de Tangentes functions as one chapter in it, like another chapter about light and blindness. The compendium works like a kaleidoscope whose dots are somehow connected. Another chapter is the one about light and blindness, which is mainly about the flash and how flash as an explosion, like the atomic bomb, is related to photography. Both inventions were amazing and frightening at the same time. The chapter includes the idea of amazement around the nuclear. One thing that was really popular in the 1950s in the United States was called “nuclear tourism”: there were a lot of events surrounding the atomic tests. I tried to relate it to the idea of the flashlight. After the explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japanese people discovered that, at a certain distance from the explosion, negatives caused by the explosion remained on walls, like a picture I found in the archives of a person grabbing a ladder: the blast printed a negative image of the ladder and the man’s body on the wall. What is important about the compendium is that it shows a phenomenon from different angles and reveals the connections between them.