Interview with Curator-in-Residence Serge Klymko

This January and February, Serge Klymko is Curator-in-Residence invited and hosted by tranzit.org/ERSTE Foundation, whose open call was specifically directed at Ukrainian artists and cultural workers.

Serge Klymko is a curator, managing director of Kyiv Biennial (founded in 2015) and founder of Emergency Support Initiative – projects he is eager to talk about. Serge, who I discover is witty and generous, opens the door to his studio with a smile and calms his small dog, Siri, who is quite excited about having a stranger in the apartment.

You are giving a presentation at Office Ukraine’s get-together today. This day, January 27, is also Holocaust Remembrance Day. What does it feel like to be in Vienna?

Vienna feels like a very welcoming city for people of all nationalities and races – especially for Ukrainians these days, of course, – but also, more broadly, in the cultural sense. So I want to say thank you to MQ, tranzit and ERSTE Foundation. There is not much happening in January, as far as I understand, but still, I have already visited a great exhibition by Ukrainian artists, While I Float. It is curated and co-organized by Sasha Horbatiuk, Natalia Gurova and Claudia Strate.

Can you talk about your work with ESI, the Emergency Support Initiative you founded in March 2022?

After the beginning of the war, we at Kyiv Biennial launched an Emergency Support Initiative helping artists and cultural workers who stayed in Ukraine and aiding artistic residencies in Ukraine for people who were forced to leave their homes in the east of the country and move to Western Ukraine. We also support documentary and artistic projects which deal with the ongoing warfare and the situation in Ukraine in general. So far, we managed to support around 900 people.

In the first month of the war, the most urgent issues had to do with simply surviving: people needed food packages, train tickets. This early period was very uncertain and hard. Later, we shifted our focus to sustainable support of the creative work of artists who stayed in Ukraine. Basic needs had been taken care of, but they still faced difficult questions: how to continue their work, how to afford a studio or materials for that, and so on.

Solidarity Screenings, which I curate and am about to present in Vienna, is a part of this initiative. It is a fundraising event which will enable ESI to support more artists.

You have already presented Solidarity Screenings in Amsterdam, Prague, Riga and Malmo. The video program of the event provides an intimate portrayal of people caught amidst war, occupation and forced migration. How were the films received? What is the concept behind the screenings?

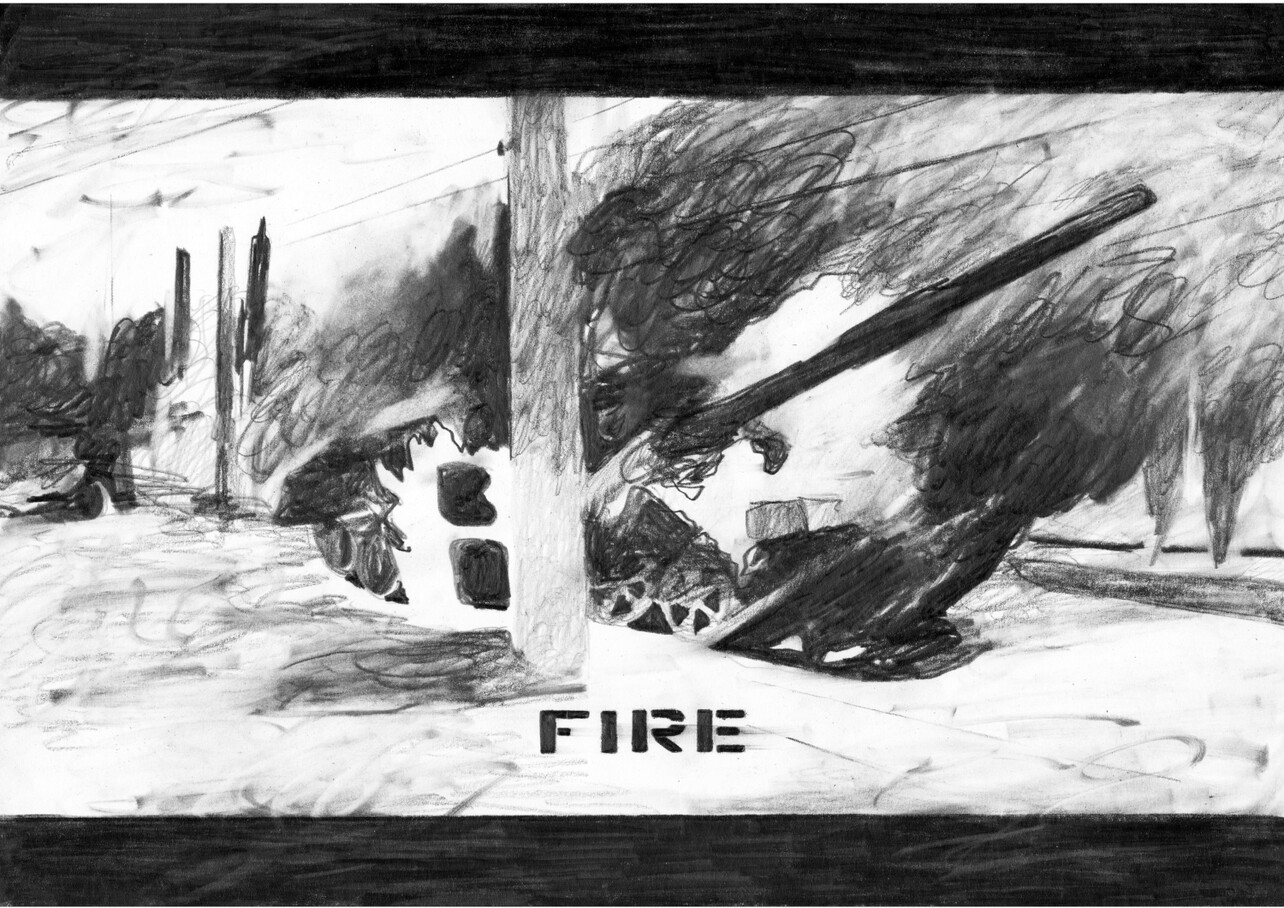

Solidarity Screenings were organised in several European cities to show the situation in Ukraine through the artistic lens. Made to preserve and build on the evidence, reflections and feelings, all of the video works have been created by visual artists based in Ukraine after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion. As to the reception of the films, I heard that many European viewers – especially in spring 2022 – cried during screenings. The films were made mostly by young artists who show what happened in their private environment, to their friends, their cities and it has had a very emotional response from the audience.

Among other things, ESI collected statements from artists you supported. Many said that at the beginning of the war they could not do anything, for obvious reasons, and when they resumed their activities, war became the main theme of their work.

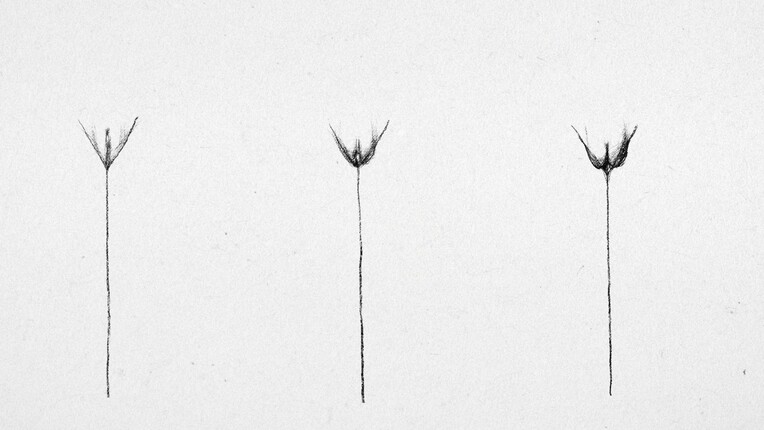

A lot of Ukrainian artists stopped their artistic practice due to two major reasons: firstly, they lost their working space, many lost their home and had to respond to unprecedented emergencies. In other words, they could not engage with their art physically. Secondly, a huge part of artists felt disconnected from their practice mentally because of enormous stress, rage, fear overwhelming them. They simply couldn’t continue their daily practice, research, work. Many people could not bring themselves to listen to music or watch movies. Normal life was suspended, and they needed to figure out how to continue living. However, lots of artists, especially graphic artists and video artists, quickly found the strength to resume their work; they did their best to speak about the situation they witnessed, film everything happening to them, comment on it with a video or an image they made. The war events even incentivised their creative activities – often in a sad and violent way.

There is this essay, “Vermeer in Bosnia” by Lawrence Weschler, which I’m reading about in Orwell’s Roses (Rebecca Solnit) at the moment. It’s about a judge from the Yugoslav War Crimes Tribunal who listens to the accounts of atrocities committed in the war and then goes to a museum to look at the paintings of Vermeer. This works as an escape, a way to find beauty, find a utopia within artworks.

The art produced before the war – as cultural references you can look to – certainly helps to regain a semblance of normality, come back mentally to things you loved and appreciated. In April/May, as I recall, there was a three-day ambient festival in Kyiv. The intention behind it was to use music, use art to heal people who suffered emotional damage. In a way, this went against the general trend in Ukrainian art at the moment, but it was very valuable to explore music and arts as healing tools. The festival was also presented as an online platform and collected donations for hospitals in Ukraine.

And that’s another important thing about art in times of war: since the start of the war until now, almost all cultural events in Ukraine collect donations for the Ukrainian army, hospitals, special equipment and humanitarian aid. People working in the cultural sphere may not have the skills to directly influence the warfare, but everybody is doing a lot of volunteer work to support those on the ground.

Many videos and calls for support for Ukraine are also shared on social media.

For the culture sector it is a way of asking for help and at the same time helping the creative field in other European countries to understand the situation.

A lot of Ukrainian artworks were destroyed…

Yes, tens of thousands of artworks and hundreds of museums were destroyed in Ukraine, in addition to being stolen and looted. For instance, before the retreat of Russian forces, Kherson state museums were looted, the artworks they housed stolen by Russian soldiers either looking for personal profit or acting on orders from up high in the chain of command.

The job of documenting these atrocities committed against culture and art, of supporting museum workers and others who were directly affected in the process of this destruction of Ukrainian legacy was first and foremost taken up by NGOs and independent activist organizations. They documented the damage and helped to save as much as possible by transporting artworks from the areas close to the frontline to safer places, to store them in Western Ukraine. Another pressing issue was helping museum and cultural workers left in occupation or on the frontline, those who stayed in museums to try and preserve their collections. So that was an enormous task taken up by several Ukrainian non-governmental organizations.

Today there is also an Artist Talk by Artists-in-Residence Tatiana Sukhareva and Olga Ramanava who share their experiences of life in Belarus and Russia. They clearly took a stance against the war, as their oeuvre attests. Some comments left under the Instagram announcement of their Artist Talk said #Russiaisaterroriststate and “we” (the MQ) shouldn’t tolerate Russians. What is your take on that?

I think canceling should not be based simply on what passport someone holds. However, if people continue living and working in Russia while pretending that nothing is happening, continue making exhibitions and remaining completely silent about the political situation in Russia and the war, they have no right to be present here. Russian cultural organizations, those still operating, directly or indirectly support the Russian government and the war through their work. At best, they act as if everything was normal; at worst, they outspokenly support the Russian war and the Russian army. The same is true for many art people, educated people.

How has the war influenced your curatorial work?

In the first months after February 24, 2022, I was completely focused on the Emergency Support Initiative to be able to help here and now, and this project is still ongoing. In summer, I started Solidarity Screenings program which was a mix of a curatorial and fundraising work, and only in winter devoted some time to a couple of curatorial projects. And I cannot imagine my work now being disconnected from the topic of war, from the situation in Ukraine.

What are your current plans regarding the Kyiv Biennial?

We have already carried out four editions of Kyiv Biennial since 2015 and plan to do it this year as well. Of course, it will be much harder than before. We will announce our finalized plans in spring but what I can tell you now is that Kyiv Biennial 2023 will be conceived as a pan-European event, with dispersed exhibitions and public programs in a number of Ukrainian and EU cities. Among other goals, the biennial aims at reintegrating the Ukrainian artistic community, divided and scattered throughout Europe by the war, to empower its actors to work and reflect collectively on cultural, social and environmental challenges Ukraine is currently facing.

Do you have a theme already?

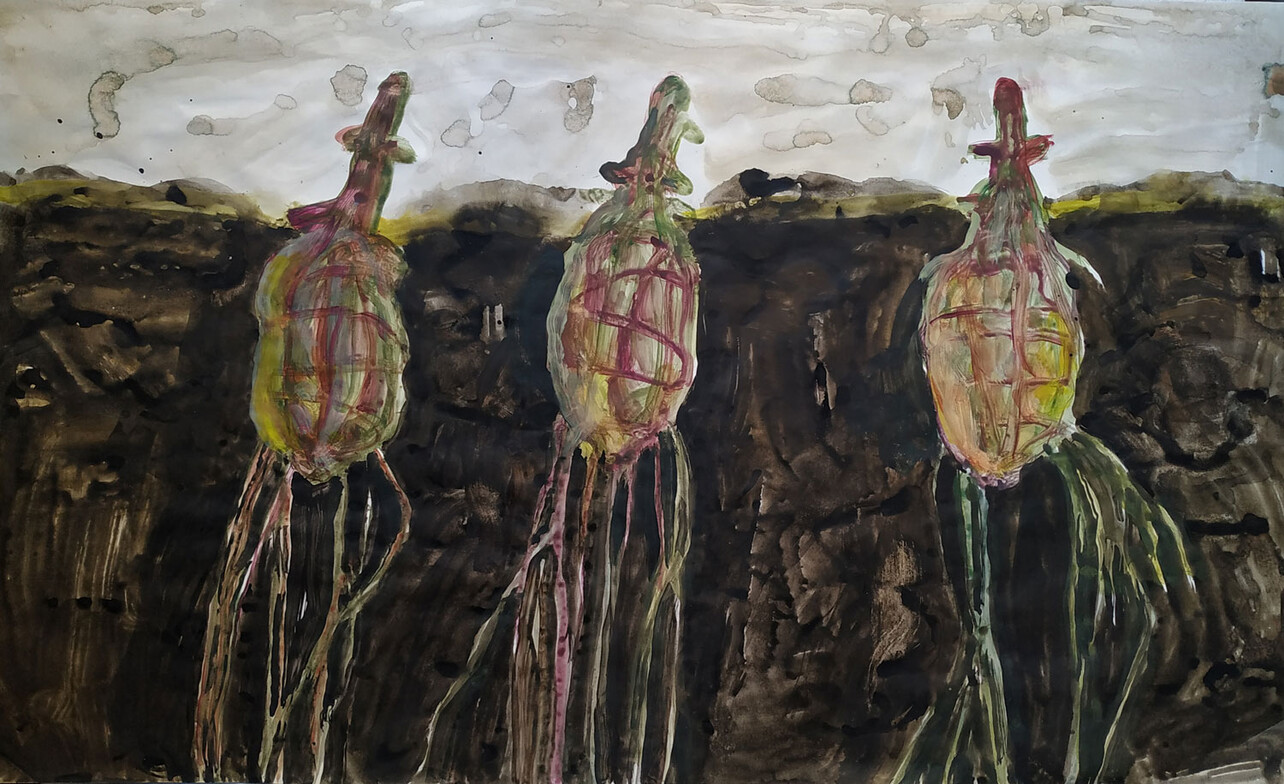

The topic of the biennial will inevitably be connected to the war and full-scale Russian invasion, sociopolitical and cultural dynamics of the crisis in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. It will also be far from one solid concept as we want to have a polyphony of artistic and institutional perspectives reflecting the most complicated situation in XXI century Europe. The upcoming edition will closely work with the issue of environmental damage of war and its consequences – devastated lands, massive biodiversity loss, pollution of natural resources, mined territories, poisoned soils.

Kyiv Biennial is an international forum for art, knowledge and politics that adopts an interdisciplinary perspective integrating exhibitions and discussion platforms. It intensively works with the architectural context of the city by involving unique buildings of Soviet modernism. Kyiv Biennial is organized by the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC), whose institutional mission is to foster collaboration between academic, artistic and activist communities; its main operations are in the fields of exhibition-making, publishing, organizing discursive projects, documentary video production and other forms of cultural activism. Since 2008, VCRC has operated as a cultural platform (both in Kyiv and internationally) with a program of exhibitions, conferences and public debates. The biennial editions include: The School of Kyiv, 2015, The Kyiv International, 2017, Black Cloud, 2019, Allied, 2021.