Cecilia Araneda: It's time for experimental to grow up and challenge itself with content

Artist-in-Residence Cecilia Araneda talks in an interview with this human world festival directors Lara Bellon and Michael Schmied about her practice.

Cecilia Araneda is a Chilean-Canadian filmmaker and curator currently living in Winnipeg. She won the exp:an:ded short film competition 2018 with her film The Space Shuttle Challenger at last year's this human world - International Human Rights Film Festival and has spent two months as Artist-in-Residence in the MuseumsQuartier Wien.

In an interview with festival directors Lara Bellon and Michael Schmied she gives insight into her artistic practice.

Lara: In your work there seem to be common themes that recur often in your films, such as memory, loss and belonging.

When I arrived in Canada, there was that first plane ride. And that day is when my memory awakes. Because of that, I guess there is a sense of a lingering loss. Where my prior life is fragments of memories I’m trying to grab on to. When my memories begin, it’s in a new place where I don’t understand the language and my family is so different, and we have so many difficulties. I think that this moment of childhood, where there was this break - there is this idea that I could have had all of these different lives and these lives have peeled off. This becomes my childhood mythology. I think we all have a childhood mythology of our own personal break or moment of awakening that we carry. So, for me, it’s flying and landing. Memory and loss is one of these things, but there is also the repeated imagery of flight and landing in my works as well.

Lara: I think it’s interesting that you talk about landing, especially as opposed to arrival.

Landing is what the endpoint of flight is. I don’t know if it’s necessarily home. Arrival is some sort of epiphany, but landing is something you need to do but not necessarily permanently. When I think about flight and landing, I think of moments of transition.

I am very conscious that I am not from here. And I say that as a philosophical place. I am always in a state of landing, and so I am aware that I am not Canadian, even though I pass for Canadian. And when I go to Chile, I am aware I am not Chilean, even though if there is any one place I belong to, it is Chile.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote, that you don’t belong to a place until you have dead buried there. So I don’t belong to Canada. I would only belong to Chile. I belong to other places, also, where my dead are - but they are foreign places I’ve never been to. So, there is also this other idea that I belong to places I’ve never been to or where I can’t speak the language. This is the legacy of being a multi-generational refugee. So I am always consciously aware that I am separate, and of not being able to grab on to things.

Michael: As the prize for winning last year’s exp:an:ded shorts competition at this human world you were awarded the participation in Q21’s Artist-in-Residence program. Do you have specific projects in mind for your time in Vienna, at Q21?

I am working on a few different film projects that I am editing and finishing, including for a show coming up in January in Winnipeg. But what I am working on while I am here is researching the displaced persons camps and sites where my mother lived the first 6 years of her life. I know the camps are no longer there, but for me it is very important to be on-site in a particular place, as opposed to place being a theoretical thing in books or photographs. I am hoping to be able to get to Spittal an der Drau and Schladming, and to be able to get a sense of space. Also because plants, vegetation and flowers have natural chemicals in them and so you can use them for organic processing, coloring or dyes and so I am hoping to be able to get some of that material to be able to work with film here and see what happens. So, the idea is that the site would be embedded into the materiality of the film. I really want to think about what I see and hear, but also include what is embedded in the earth there, and what is coming out from it.

Michael: You are also the co-founder of a Latin woman artist collective. What is important to you in this aspect of your artistic work?

It’s difficult to navigate a career as an artist, as a lot of opportunity is handed down through who you know. There are many things that are not possible to learn through academic study, because it’s often about information gained through personal connections. I am aware that experimental filmmaking in Canada is a very privileged practice. The experimental filmmaker’s job is to react against the film industry, but in adhering to this idea and declaring analogue film as holy, it becomes a new kind of art cult. In doing that, it closes itself off to new contributions, new expansions and new languages, because it doesn’t consider content as experimental film or art.

As a result of what I see in experimental filmmaking, I have been thinking a lot about exclusions of access and who gets access into the institution as a whole – whether academic or formal art; what gets considered serious art, versus what is disregarded as craft or hobbyism. So, I am working with Latin women, a group of artists working at different stages in their careers, who only have in common a cultural point of departure. We work within a process of professional development, to bring together learnings and exchange, to help each other in the context of a whole initiative that is not institutional outreach.

Lara: You work with a lot of hand-processed, hand-printed and coloured techniques on 16mm film. What has informed your style?

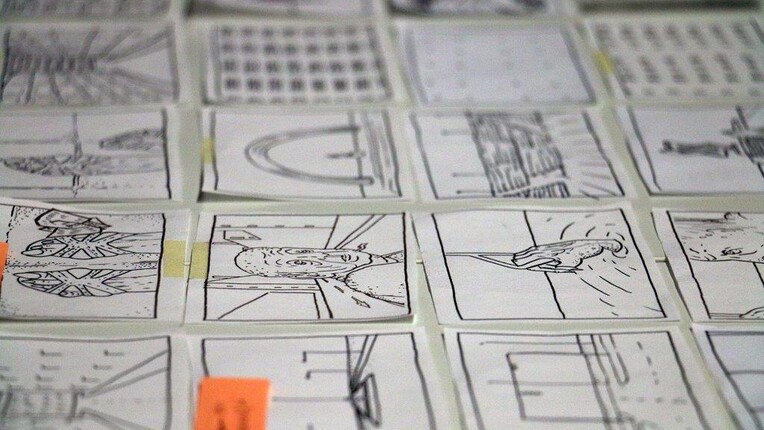

The Film Farm just outside of Toronto, and its founder Phil Hoffman in particular, had a very big influence on me. It is a week-long analogue filmmaking workshop. Hoffman has influenced not only the process of how I construct content or build a story, but also how I consider images and how I manipulate them, so that they become something that feels more honest to me. The first time I went to the Film Farm, Hoffman challenged me to reflect more on the process of how I make films, and it had a big effect. I’ve attended the Film Farm three times in the past decade.

All of my experimental films are not really abstract. There is always something an audience can hang on to, even though it might seem very random. And I think this sets me apart from a lot of other experimental filmmakers in Canada, who focus solely on technical experimentation. I am not married to analogue - I just see analogue as a tool for storytelling. I want to communicate and so I am trying to bridge how I see things and how I formulate my ideas with making work that is somewhat comprehensible to an average person. Something to hold on to - so you do not have to be an academic in experimental film to understand what I am doing, even though you may not understand the technical processes of how I work or how long it might take me to do this. That is where my experimental documentaries come in. This is how I deviate from the experimental film scene.

In this space, there seems to be a notion that doing art for art’s sake makes more sophisticated art. Whereas if you get into content, this becomes ordinary or less important artistically. So, there is that big discussion around what constitutes meaningful art. Am I even an experimental filmmaker if I introduce content as a critical element of my work? I am an experimental filmmaker, but I think there are a lot of people in the experimental film scene who don’t view me that way because I have content.

Michael: As part of this human world – International Human Rights Film Festival you were holding a masterclass with the title: Can the experimental be political? What are some of the questions and issues you were raising in line with this?

Canada is a colonial nation, there are about 40 different Indigenous cultures in Canada. So it’s not really a white country. The Indigenous population where I live, in particular, is proportionally very high. However, what ends up happening in experimental filmmaking in Canada is that it is a white practice. And so when I say that, this also means it is a practice of privilege. There are not that many non-white people in experimental filmmaking in Canada. Those who are not white, are often people who pass as white - like me. And there are almost no Indigenous creators. It’s really a white space.

Experimental filmmaking also tends to be handed from person to person. There is very little opportunity to enter into it without mentorship, and so you need somebody to allow you to enter into it - and commonly mentorships are facilitated more easily if somebody understands your cultural context. And so, experimental filmmaking in Canada is very separated from what is happening in Canada and as a result, I have a very difficult relationship with it because it is so exclusionary. Art for the sake of art becomes the domain of the experimental filmmakers; and the minute you use experimental filmmaking to reflect cultures or experiences separate from the mainstream, this is where you deviate from it.

I have recently been researching a number of filmmakers in Canada for curatorial purposes. Franci Duran and soJin Chun are two of them.

And so I wanted to use the master class to talk about this as a through-line – what is the experimental and what is the political? Is there another way of entering into a process that considers bridging that gap? What is the responsibility of experimental film practitioners to bridge that gap - to find mentees and find a new way of working within the political? Experimental film can be used to express a lot in a very condensed period of time.

Lara: I think it's interesting that you talk about a responsibility inherent in filmmaking, due to the fact it is a practice of privilege. Has this awareness changed over the past years?

Social justice documentaries can also be very voyeuristic. They tend to be outsiders coming into different places, with a very voyeuristic lens. So, is there a way to create a more personal experience, to join something together more artistically, so people can make documents of their own experience? In a way social media almost reflects this better, you see a new social media language being created, which is starting out to create a new medium of meaningfulness within the social justice domain.

I think it’s time for experimental to grow up and start challenging itself with content and with the politicial, with cinema that can move beyond a suburban, middle class experience of privilege. That’s what I wanted to talk about, and talk about filmmakers who challenge this idea.

And when I talk about mentorship within experimental filmmaking, I do think it is the responsibility of experimental filmmakers at a certain point in their careers to also find people who do not look like them and do not come from their same culture, to exchange. I think that is part of the bridge-building that is inherently the responsibility of an experimental filmmaker.